It's just a bit too grim for Chloe Sevigny apparently, but if you happen to be up Manchester way on 23rd February then GRIMM UP NORTH have a great arthouse horror double bill coming your way ..

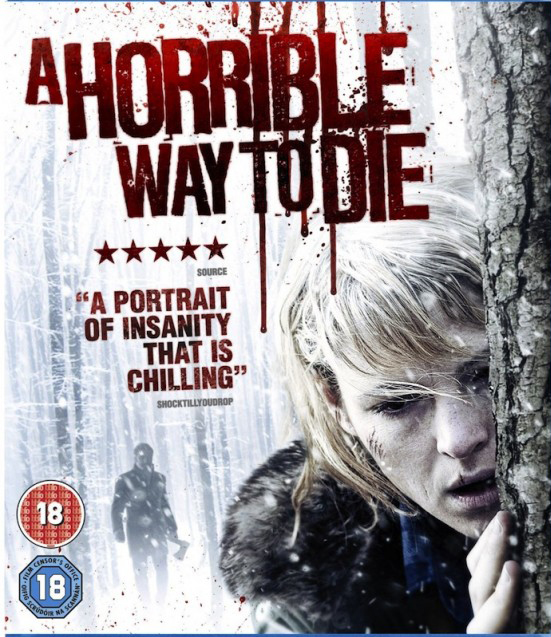

A HORRIBLE WAY TO DIE. Adam Wingard’s unrelenting and violently modern psycho thriller that is just as disturbing as it is powerful. As an Award winning festival favourite, Grimm are proud to announce that we will be screening the film before its official UK DVD release (in March).

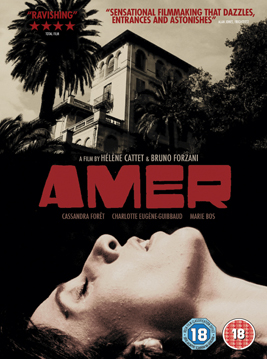

AMER ‘This is art-house horror, a pure cinema for connoisseurs, a return to late-19th-century decadence.’ An homage to the great works of Argento and Bava, Amer is psychosexual thriller that captures the zeitgeist of 70′s Italian horror effortlessly.

Find out more and order tickets here!